INTRODUCTION TO ‘NONPLACE’

The all-encompassing awareness of previous decades and the easy access to the audio archive has ultimately made production obsolete, in particular when all attempts to sound contemporary can be found to have already been made.

An Introduction to Nonplace

BURNT FRIEDMAN & JAKI LIEBEZEIT / SECRET RHYTHMS

“There’s something about Burnt Friedman’s music that’s impossible to pin down between genres, styles or cultural cues. The German artist’s music exists beyond any zeitgeist or totemic musical pole in an unifying artistic language all onto its own. With an acute focus on rhythmical structures to an almost obsessive degree, Friedman’s work operates on the fringes of electronic, experimental music, reinforcing a pervasive, primordial musical form that exists through and inspite-of every and any musical tradition and stylistic trope.” Jaeger, Oslo 2017

Over the past 12 years Secret Rhythms has become the leading Nonplace trademark. Central to the secret rhythms concept is Liebezeit’s radical “drum code”. Jaki Liebezeit (1938-2017) numbers among the world’s foremost drummers. Between 1968 and 1978, playing as a founding member of the legendary Can, he produced rhythms to be heard nowhere else, anticipating by many years the loops of modern club music. His delicate and peerlessly precise drum sound is audible in countless studio productions by a range of artists from Conny Plank to Jah Wobble. But by the early 1990s Liebezeit felt he had exhausted the possibilities of conventional drums. He made a radical break, and began to re-define, or re-invent, what drumming was about. Jaki Liebezeit: “That explains why I’ve meanwhile abandoned conventional drums, the standard American kit. I looked around for something different, and now I just play drums. People keep saying my drumming is so reduced, but there’s nothing minimalist about the way I play, I just leave out the superfluous stuff.”

Simplicity became a core principle for Liebezeit and collaborators like the Cologne formation Drums Off Chaos, or Burnt Friedman, who is noted for his richly detailed, groove-heavy productions. Less is known about his activities in the period from 1978 up to the mid-1990s, when he began to make his own instruments and took up the drums, initially with no thought of electronic music. He was searching for a method that would allow him to play although he lacked any knowledge of music or what it was supposed to be. From the first note on he recorded all his ad hoc compositions, since these attempts were useful for the purposes of learning.

Friedman engaged in the experimental aspects of music from an early age, using toys and household items in a “primitive” pursuit to create music. A drummer in various projects throughout the nineteen eighties, his focus, like so many of his peers, shifted towards electronic processes during a time when musical machines were commonplace and allowed musicians to start exploring music outside of the limits of natural and institutional human impulses. Through several solo projects and collaborations, Burnt Friedman created music throughout the nineteen nineties, with his largest contribution coming via his Nonplace Urban Field project in which he first established the idea of music with origins from- and designs on a non-place. Nonplace is music that lives outside culture, identity and music politics as a form of artistic expression that moves “beyond a culturally determined reality”. Jaeger, Oslo 2017

NONPLACE

In the early 2000’s Friedman & Oke Göttlich established the label, Nonplace and Friedman embarked on the defining solo project of his career as Burnt Friedman. It’s as Burnt Friedman he joined forces with Jaki Liebezeit, the legendary drummer for the penultimate avant-garde rock group CAN for five albums as the Secret Rhythms series before Liebezeit’s untimely passing in 2017.

Friedman’s live-and-studio project with Jaki Liebezeit, must be viewed as intermediate phases in an on-going process. They are not finalized, completed pieces that permit no further alteration, nor do they correspond to the idea of an original with unmistakable identity. On the contrary: permutability is their salient feature, and they are built according to a plan that follows natural laws.

The attention shifts away from the individual contribution of any one instrument or player, away from the defining hook and towards the micro-elements of the groove with its patterns of linkage that inhabit the musical forms. In music of this kind, the role played by subjects and grand gestures is no longer central. excerpt from (Bokoboko) and (10th Anniversary Compilation) recording info sheet

“With today’s vast libraries and idiotic sub-divisions of genres, an artist’s original expression is doomed to fall somewhere in between countless filters. I think that listeners get the impression that everything in music has now finally been developed and is unalterable and petrified. During the late ‘90s, with Anglo-American pop and dance music, and their sub-cultures, the process of feeding and accelerating modernity may have come to an end point where one cannot be louder, faster, noisier, slower, lower, higher, and so forth. It’s created a standstill where everything seems retro from today’s point of view.” (edit from XLR8R 2017)

RETROMANIA/HAUNTOLOGY

Friedman: “Mark Fisher had a habit of confronting his audiences with a telling thought experiment. He asked them to imagine how someone with a good knowledge of music of the 90s or earlier would react if we played any randomly selected pop track from today, let’s say from 2015. That would be an artifact from the future. Fischer asked: Wouldn’t the reaction illicit a sense of incomprehension at just how familiar it all sounded? It would be anything but a ‘future-shock’. “Is it really gonna sound so familiar?” (Mark Fisher) He compares the results of this thought experiment with the everyday reality of the 70s, 80s, or 90s and contends that, in contrast to the creative standstill we know today, there was a rapid coming and going of musical concepts. Fischer sees this as a defeat for the vibrant network of subcultural contemporaries, as a loss of the collective presence of mind. In those days, the music that was oscillating in a state of “permanent obsolescence”—often in short cycles of a few months—and preserved as a sign of the times in musical codes, has gone in the completely opposite direction now becoming a obsolete permanence.

“Staring around the year 2006, it became clear that we were entering a new form of cultural time, at least in pop music. For many of us the developments in music was a way to experience and measure temporality. Thus, we learned to associate particular historical moments with particular sounds (…), it was, moreover, clear that the connection between certain sounds and particular historical moments broke down. The cultural time had lost its special character. Similar to how public spaces or shopping centers had become indistinguishable, anonymous, commercial, homogenous ‘non-places’, the cultural time became a ‘non-time’ ”. ( “Wir Leben In Einer Nicht-Zeit” Interview by Christian Werthschulte of Mark Fisher, in Testcard 23, 2013) The ‘question’, “How can we tell now 2006 apart from 2011?” clearly condenses the problem at hand. Fisher located the cause in the ever-increasing digital dementia and the loss of free time. “The more the dispersed attentional economies of communicative capitalism have taken over life, the more there is this difficulty in grasping a sense of historical moments in which we live.” (Mark Fisher)

Mark Fisher lamented the ‘state’ of things, the failure of music to achieve a presence of mind, that all the efforts to get beyond the status quo were in vain, that the mainstream had not transformed itself; He mourned musical condensed utopias that now haunt us as a “lost future”. The current, in the best case, ‘radical’ music of the day was at once a form of resistance against the missing consciousness in the mainstream; it wasn’t just made to make the listeners comfortable. It could and was even intended to be overwhelming and painful. Instead of lulling into complacency, it could be an eye-opening medium that takes a critical approach to reality. For a long time now, there have been countless empty simulations: isomorphic tracks that are indistinguishable despite being separate in time by about 40 years in each direction. Simon Reynolds has encapsulated this phenomenon with the term ‘retromania’, While Jean Baudrillard had already predicted the ‘vanishing point’ in 1984. “Today you can go into a café and Blondie is playing on the stereo. That would be like hearing Benny Goodman at a café in 1980. In a certain way, the 1960s were at the time even further away than they are today. This goes along with the massive lowering of cultural expectations. No one really thinks that there will ever be another truly great record.” (“Wir Leben In Einer Nicht-Zeit” Interview by Christian Werthschulte of Mark Fisher, in Testcard 23, 2013 )

Or is it the case that the pop and jazz avant-garde in the 60s and 70s was so brutally futuristic that this music will always sound contemporary to us? The all-encompassing awareness of previous decades and the easy access to the audio archive has ultimately made production obsolete, in particular when all attempts to sound contemporary can be found to have already been made. Mark Fisher assumed that this contemporaneity, presence of mind, or the recognition of a time stamp—of a concretely informed sound from another time—is something that we can no longer expect an audience today to be able to hear. (Mark Fisher committed suicide on January 13, 2017, nine days before Jaki Liebezeit died.)

Friedman:”Has the vocabulary of the popular—and for lack of a better term—modern ‘Western’ music now finally been spelled out? Has the ever more hasty striving to move forward led to a music that is ‘starving among this embarrassment of riches’ (‘verhungert in der Fülle’) ? Is it possible that in this drive forward towards refining and destroying musical articulation in academia and popular culture an increasingly more bizarre form of ‘louder, softer, higher, further, faster, slower, newer, more intense, thicker’, etc. has become irreversibly and imperceptibly cemented in the body as measure-based ‘accentual’ rhythm that tends toward isometric forms? In the burgeoning confusion about the freedoms that have been achieved, the corresponding theory seeks to break free of its phenomena. In contrast to this, a nature of ‘polyrhythms’ is perceived.”

Excerpt from “Persistence Of Duration”, in “Jaki Liebezeit Practice And Theory Of A Master Drummer”

UNIVERSAL / TRANSCULTURAL

Friedman: “There are alternatives: not to take music as a hostage for all sorts of profane purposes. Allow music to be useless, because herein lies its greatest power. Avoid pinning it down to territories—music tends to travel beyond territory, it is motion based and predominantly represented not by cultural entities, but either individuals or small groups of people.” (edit from XLR8R 2017)

This polyphony of non-places also includes the spirit of sound explorers such as the musical-ethnological practitioners Hartmut Geerken and Roman Bunka (Embryo) whose visions and musical activities refuse to succumb to reductionist and essentialist staging.

Friedman intuitively pits the liberating power of noise, of über-mensch-maschinen music, against those cultural landscapes repeatedly automatically inscribed into music.

Odd beats and random technical defects – that is to say, disobedience (“Un-gehör-sam”, Johannes Ismaiel-Wendt) – are pitted against the normative interpretational supremacy of musical world maps. excerpt from NON38 (Cease To Matter) recording info sheet

Judith Becker: “The arts are not considered as vehicles for personal expression, media through which the ‘artist’ presents his personal world view. On the contrary, it is the performer/creator who is the vehicle through which the traditions are continually renewed and vitalized. (…) There is practically no opportunity within the traditional arts for one individual to become a ‘star’ ”. (Judith Becker discussing the Javanese concept of the Gamelan as a manifestation of a supernatural, charismatic power and how the performance by ensembles today still embody this essential attitude, in: Arthur Simon, Kategorien des Musiklebens in traditionellen Kulturen Afrikas, Asiens und Ozeaniens). Excerpt from “Persistence Of Duration”, in Jaki Liebezeit “Practice And Theory Of A Master Drummer”, due Nov 2019

Friedman: “I am amazed how current identity and gender politics in prospect for equity, inclusion and diversity is analogously reflected in the pop history by an increasing “intersectionality” of music-styles, from when individual freedom broke lose in the 60s.

Imagine also that on the other hand, people were talking of “African music”, etc. as if it was a category. The only way I found to oppose the struggle with natural diversity by releasing more and more subjective categories, I finally learned to address the matter on the level of the individual.

Music does come from small groups or individuals and they might claim it came to them from the gods. In the standpoint of an artist as well as in the position of a scientist, their utterances have no obligation to culture, by which I don´t claim they do not have any cultural imprints at all, we are naturally born cultural beings. Yet, music, science (math) and theology appear beyond a culturally determined reality, hence, those disciplines are negotiated on a trans-cultural scale and not by cultural notions of territory, biography, bloodline, skin color and traditions even.” edited excerpt from an interview with Jaeger,Oslo 2017

Friedman:”None of these territorial attributes and essentialist characteristics would help understanding the nature of musical mating, especially in a world where almost everyone has immediate access to sound sources from any time in recorded history and territory.” excerpt from inverted – audio interview Peter Adkins 2015

“One would not expect a mathematician or chemist [to] argue about heritage, environmental conditioning and cultural background, but to make propositions on a universal level. That kind of science is a trans-cultural activity, otherwise it would be useless.

It’s a conundrum, because tribal music is often considered to represent fixed local cultural attributes, although the instrumental musical material in sound and form was operated on with universal set of laws of rhythm and tuning that stand comprehensible beyond the limitations of locality, local language and heritage.” (excerpt from inverted – audio interview Peter Adkins 2015)

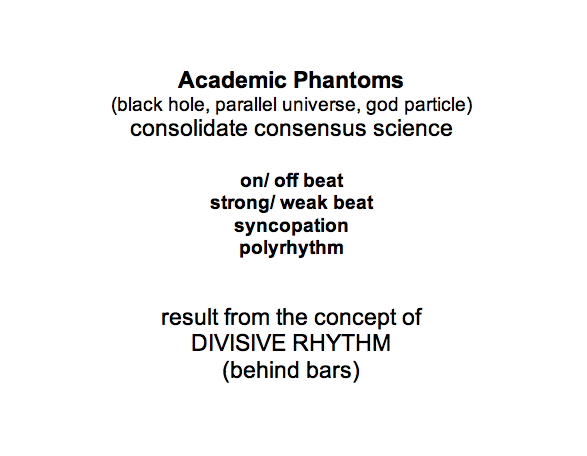

RHYTHM

Friedman: By finding the commonalities of how rhythm is dealt with in musical groups spread out in locales all over the world and working different periods, Jaki Liebezeit was able to arrive at a transcultural praxis-oriented theory of drumming. Unencumbered by arbitrary concerns, the natural conditions for drumming were free to develop. A controlled regular movement yields stable interrelated time intervals with the least expenditure of energy. ‘Listening’ to these proportions, listening to sound would be objective ‘listening’. It would be a dehumanized ‘listening’ to not also seek the conditions for the production of rhythm in culture. Especially when playing at very fast speed, one wants to know where it’s going. Therefore, it becomes clear when the classical Greek ‘rhythm’ is not just translated as “flowing” but also as “support and firm restriction of movement” (Werner Jaeger, Paideia 2, 1936). This understanding of rhythm must also find commonalities among the ‘anomalies’, i.e. also among the ‘crooked’ rhythms.

In drumming, in collective production of constructive interference, all those involved become attuned to one another in a sort of resistance against arbitrary dictates. The offer of freedom can be seen as a way to get in touch with necessity. The attempt is made to reach this through one’ s dedication to a mode of action, the drilling of a method, not through individual cunning or soloistic prowess. Much more important is the constitution of a community of listeners who don’t have anything to show off. By contrast, imagining artists as liberated people would mean to confront oneself with mentally disturbed people who disavow their cultural influences, their flesh and their bodies.

Excerpt from “Persistance Of Duration”, in JakiLiebezeit “Practice And Theory Of A Master Drummer”, due Nov 2019

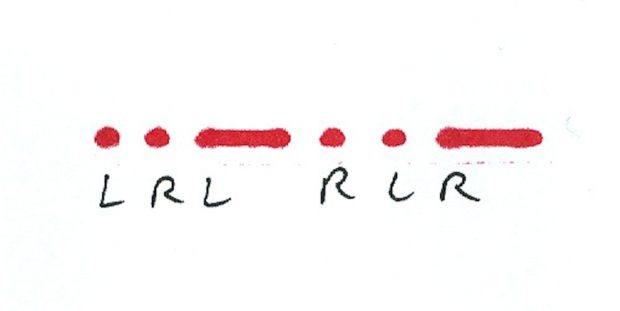

Friedman: “The rhythm language that I use originates from Jaki Liebezeit. It’s a motion formula that applies to all the instruments, all the elements in the music. They all follow the same…”

T.Monaheng: “Pattern?”

F.: “It’s a pattern if you like, but it’s more than that. It also gives you a hint to move properly balanced. It requires left and right, a plus and minus pole. It’s not something that could be memorised or read from sheet, it needs to be felt. Each stroke as well as its omission is felt. With those empirical findings on mind – I’d say the natural motion patterns are the same anywhere in the universe, since the patterns are derived from the law of the octave – which is not man made -, meaning doubling or halfing (1/2/4/8/etc.). Usually, to all the regions I come to, and especially in Europe, we have one predominant rhythm.”

M.:”Is it the 4/4 pattern?”

F.:”Yes! It seems like a harmless statement, but in fact it’s been drawn into everyone’s muscles. If another natural rhythm pattern appears, people tend to not understand it, especially people who are trained in music. It’s actually easier for people who have no knowledge about the ingredients to be more at ease with these irregular grooves. It’s just a different symmetry that incorporates longer cycles than four. On this continent we can often find – for instance on the West African coast – a constellation running on 12 (3×4 or 4×3 or 5/7)”

M.:”Or even 6/8 patterns?”

F.:”You say 6/8, but this is already Western thinking, because how would you divide 6 by 8.It doesn’t result in a whole number.

It’s one indication that proves how obsessively imaginative notation and musical thinking is, because it doesn’t account for the motion; it doesn’t account for a rhythm coming from somewhere, and going somewhere. It doesn’t account for the cyclic (periodic) nature of rhythm.”

M.:”How do you mean?”

F.:”Cyclic, as opposed to rhythm and notation in bars. That’s called divisive rhythm – hence why we have sections in bars. A bar goes from a start to an end-point, and then repeats. But a cycle doesn’t have a start and end-point; it depends on your perspective, it accounts for someone who perceives the music. It’s not simply a picture of the music, it’s an abstraction of what’s in motion; it’s just an abstraction. With what we do, it’s much simpler; constructions like 6/8 or 3/4 are a big handicap in understanding how this music works. They are especially a handicap for people who try to drum to it. So what we have is 5/5, 7/7…”

M.:”But that’s 1.”

F.:”Why is it 1? 5 divided by 5 makes 5 equal components of the rhythm. It’s 5 equal components, which is 1 of course! So what I’m saying is it’s very simple, just divide what is called a bar into equal parts, and not into something that’s not real. It might be real for classical music, for instruments that follow notes. It defines the length of the note. But with rhythm you don’t have that. You have either a strong or a quiet impulse; you have impulses of almost the same length. Maybe you can have a deep and a high tone to account for, roughly. But that’s not needed, it’s superfluous. If you put it cyclically, you don’t have an accentuated or an un-accentuated part of the bar. The beginning of the bar must not be accentuated, not necessarily. That results in the natural motion pattern.”

edited interview from Mahala, T.Monaheng 2013, Johannisburg, South Africa

Friedman: “Usually when you go to a concert to see a band, they will normally play everything in the same rhythm—four or eight beats to a bar, probably. Maybe in the field of jazz one is more likely to come across various rhythm modes. If it changes, it’s very hard for the listener’s consciousness to switch from one to another. Maybe the old groove still resounds in your mind, and you then enforce it on to the next rhythm scheme. I assume that most people probably don’t get the groove, it’s a common thing. It would happen to me too, but I have a trained ear. It’s only on a rare occasion that I don’t recognize the groove, and it becomes impossible for me to mix the tracks. Everything turns upside down. That means that the music informs me in a different way—maybe because I missed the cue point by pushing the fader at the wrong time, so it didn’t start from the beginning. Perhaps I had perceived it as an accent that drew me to the beginning of a loop, so I was coming at it from a different angle. It can be quite interesting sometimes, so I play with that. If you have longer cycles, then that stuff happens. I like the effect of rhythms falling apart, I like that surprise effect. Even I get to the point of the music being unpredictable. With techno grooves on the other hand it’s almost arbitrary. The beats can be divided by two, so almost any combination of sound, noise and chords on that beat formula can work. It’s like a metronome, not really a rhythm.”

XLR8R: “Do you feel any connection to that kind of music? How does it impact on your when you play at those kind of events?”

Friedman:”I have some metronomic elements in my music—a straight bass drum or hi-hat, very regular stuff. That’s my way of assimilating to trance-inducing, beat driven music. I use metronomic elements on odd grooves. It’s usually considered polyrhythmic, but actually it’s just a metronome. It’s not an alien element, rather the pulse of the music. Whether it’s low tempo or quick tempo, it’s just a pulse. In any rhythm, it’s always there, you just don’t hear it.” excerpt from an interview with XLR8R 2017

Allegedly the sound of one-armed bandits inspired Paul Desmond to compose “Take Five”: “It was the rhythm of the machine which influenced me, and I really only wrote the track to get the money back I lost that night.”

Although jazz offers examples of odd time signatures stretching back all the way to Lennie Tristano in 1955, for example, or Dave Brubeck and Paul Desmond in 1959, fundamental differences persist in the way these rhythms are perceived. Terms like downbeat and offbeat, polymeter or syncopation point to theoretical inconsistencies. They demonstrate that the notion of a uniform, dynamic functional principle is alien to western thinking.

Watching Liebezeit play his drums, or following the developmental path of the Secret Rhythms titles, it becomes possible to understand that the rhythmic formula is comprehended as being circular – in much the same way as in traditional or neo-traditional music in non-western spheres – as opposed to linear and progressive. The formula is derived from a recurrent, necessarily balanced body movement from which every impulse originates as something sensed as opposed to noted down.

Once these basal motional patterns have been transposed to the memory of the body, they can be effortlessly transferred to any desired resonance box, string, drum, xylophone or piano. They are in tune to begin with.

This formulaic principle, which can be represented with just two signs, or translated into simple digits, can also be grasped as an energy structure according to which the individual (or an infinite number of individuals) is synchronized. Analogously, all the instruments played on Secret Rhythms 5 are synchronized to the principal motional formula.

excerpt from NON35 (Secret Rhythms 5) recording sheet info

Friedman: “In my estimation Western culture focusses on individual achievements, the virtuosity of players, the depth of the voice, etc.. A telling quote from the radio, introducing a recent classical live recording: “Beethoven´s piano pieces are the Mount Everest of chamber music” or the term “Hi-Speed jazz” prove to me that innovation and originality is closely related to a singular live performance, a rather sportive performance. However, in the West we pick up on the significant differences between the artists, establish parameters of measurement for soloists.

The spectrum of achievements also includes notions of agitation and resistance, festival motti under the banner of “A-tonal, Un-sound, No Musik, Dis-continuity” prove that the old struggle with an hallucinated oppressive authority is still going.

I question: Free Jazz from what?

Isn´t it sophisticated enough to set a tune right, play in tune and get things properly in order to make music work?

Traditional techniques of music-making remain unnoticed or simply do not belong to Western cultural standards. As a consequence, to me, the most radical original music to play today is “traditional”(inherited/given) music, without a territorial music-idiom, an emphasis on the individual or notions of deconstruction or destruction.

A self doesn´t seem to be the center of interest in a type music that was given, inherited, mutated over the centuries, therefore, an author is not immanent. The concept of originality and with it the idea of authorship is obviously at stake. As it was in the early 90ties when techno music confronted the same issue with the hyper-speed production and release of self-similar white label 12″s, which in a way seems to have been the Western equivalent to ritual music.”

edited from an interview at Tokafi, by Tobias Fischer

“…lets acknowledge that a drum can not be improved. It would be naive to think, that the playing got any better over thousands of years. To keep up with the training is not easily maintained, especially in the format of groups and a cultural shift towards a DJ as a liberating force behind the music.” Jaeger,Oslo 2017